My New Year's resolution is to be in full compliance with copyright law. And frankly, I've found that it is much more difficult to comply with this law than I ever imagined. I've been sending out dozens of copyright requests all week and crossing my fingers that everything is going to work out for the best. It has me incredibly nervous!

I used to believe that it was okay to copy just about anything as long as I was using it in a classroom and for educational purposes. Unfortunately, that's not true. Like me, I think that a lot of us may potentially be ignorant of how copyright law applies to us as educators, so I thought I'd write a blog entry about this topic in the hopes that we all can be more compliant.

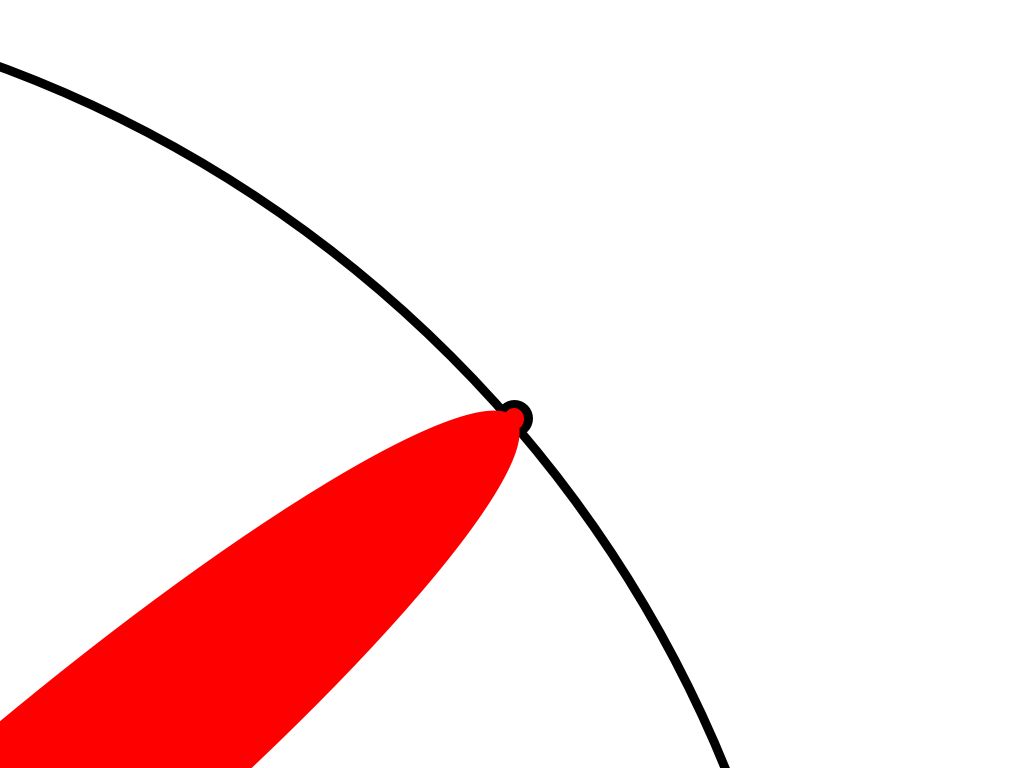

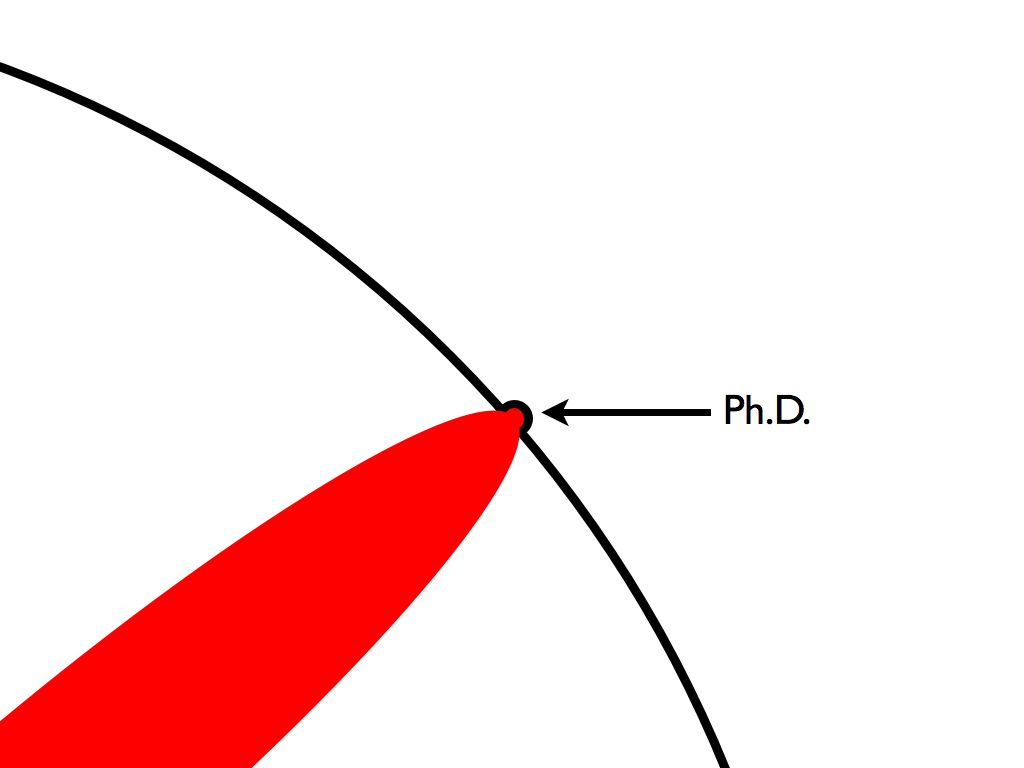

According to my research, use of copyrighted material for educational purposes falls under the category of "fair use" under the copyright law. There are four criteria that must be met in order for something to be considered fair use:

1. Purpose of Use

It is okay to copy something for educational use, but it is only appropriate if the copies are used spontaneously. For example, let's say I decide to copy a copyrighted article to share with my students in the classroom the day before one of my lectures. That is clearly spontaneous. However, if the next semester comes along and I say "Hey, that lesson plan worked great and that article was perfect!", I no longer have the same rights. If I copy that article for my students the next semester, it is no longer spontaneous and I am guilty of copyright infringement. It is okay to use an article temporarily and spontaneously. But an article should not be put into an anthology of any kind or distributed to students for more than one semester until you receive explicit permission from the copyright holder.

2. Nature of the Work

I'm not totally clear on what this means, but it has something to do with whether the work contains well-known facts and ideas (which are not copyright-able, but are part of public domain) vs. how much of it is the author's own insights and expressions in it. This is something I'll probably need a lawyer to explain to me some day.

3. Proportion/Extent of Materials Used

This refers to how much of the work you are using (e.g. what percentage of the work you are using). For example, there was a case where a teacher was found guilty of copyright infringement for copying 11 out of 24 pages from an instructional book. If you copy a paragraph from an article or a book, you're probably okay since it's just a very small portion of the overall work. However, copying a chapter or more from a book becomes questionable and can get you into trouble.

4. The Effect on Marketability

This is by far the most important of the four tests for fair use. If copying and distributing the materials will result in a reduction of sales for the copyright holder, it's illegal. For example, let's say I decide not to use the Allyn and Bacon textbook in my class because I don't feel I use enough of it in my curriculum to justify the expense to my students. If I decide to copy a few graphs or pages from the book and give that to my students, I essentially reduced the sales for the Allyn and Bacon textbook. That could get me into hot water.

One other thing I didn't know is that you must include the copyright notice whenever you copy something for a student. It is not enough to give attribution.

If you want more information, check out this helpful website: A Teacher's Guide to Fair Use and Copyright. Also check out UVU's Course Reserve page to see the copyright laws in action at our school.

***

Yikes! I don't know about you, but this stuff just floored me when I learned about it a few months ago. This week I've had to send out copyright permissions to: the Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr., Scientific American, the journal Science, The New England Journal of Medicine, Disney's Wondertime magazine, and W.W. Norton who publishes They Say/I Say. (By the way, that last one is a long shot, but one can always hope.) I've also rewritten many of my handouts so that they are purely in my own words and using my own original ideas. It's been quite a mammoth task. Wish me luck!

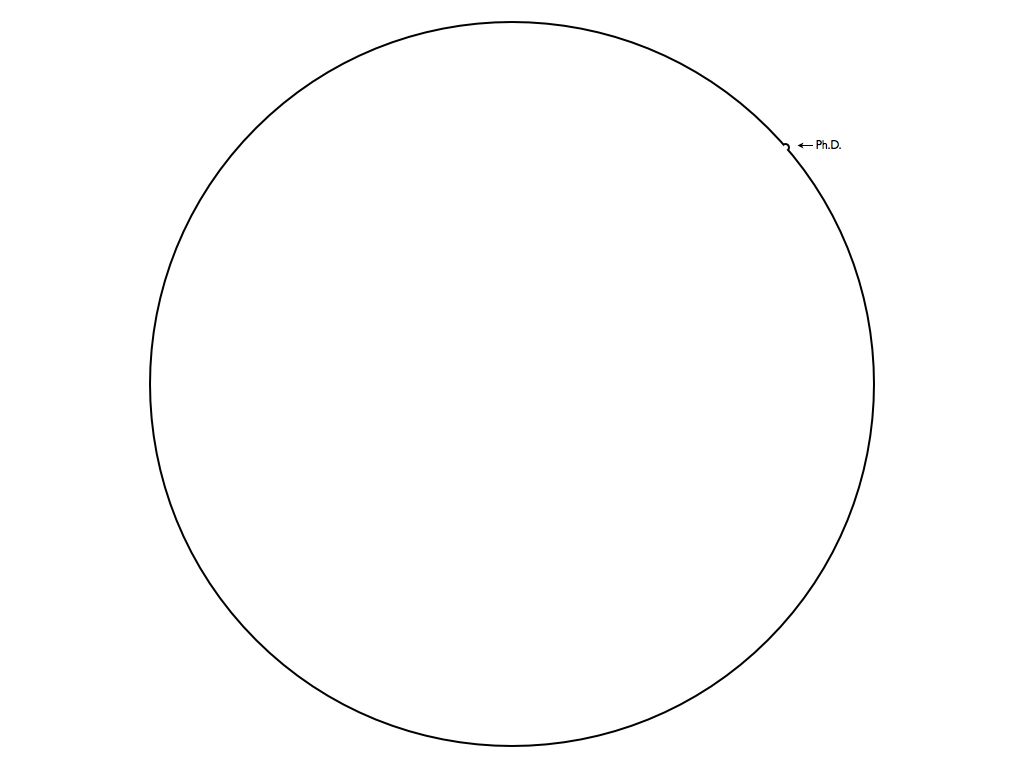

P.S. The image above comes from Gideon Burton's Flickr photostream. I'm pretty sure that since we're friends, he won't sue me for it. :)