I thoroughly enjoyed John Goshert's presentation at the beginning of the semester about deepening the level of our students' critical thinking through scholarly articles. I don't want to sound like a brown-noser or anything, but I genuinely thought it was inspiring. As a result, I've made some modifications to my curriculum this semester in order to emphasize scholarly texts a lot more.

I added an extra day to my curriculum to "champion this cause," if you will. Since I taught my lesson about engaging with scholarly texts last Wednesday, I decided to blog about how I approached it in case it could possibly be helpful to you.

I introduced the lesson by showing a brief PowerPoint presentation to kind of get my students thinking about the big picture of why they should do scholarly research. The presentation was based on a blog entry by Matt Might at his blog http://matt.might.net. It is called The Illustrated Guide to a PhD. Might has given permission to reproduce this blog entry for non-profit purposes as long as they give proper attribution to him and follow these requirements. Here's a reproduction of the presentation, with my additional comments in [brackets]:

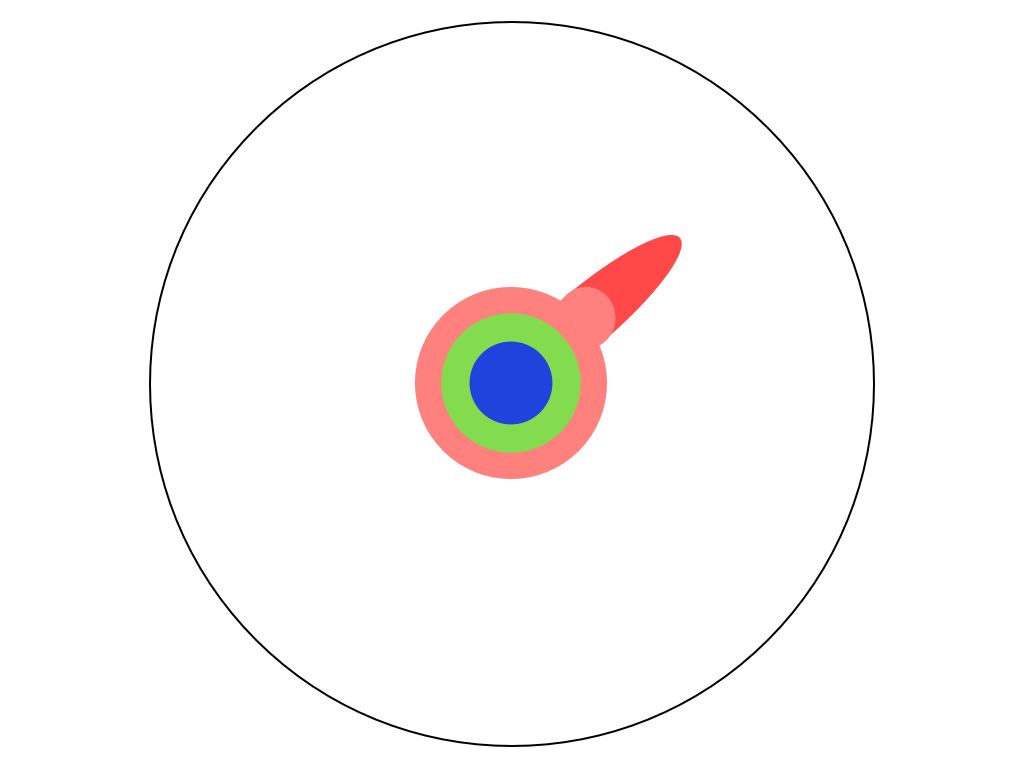

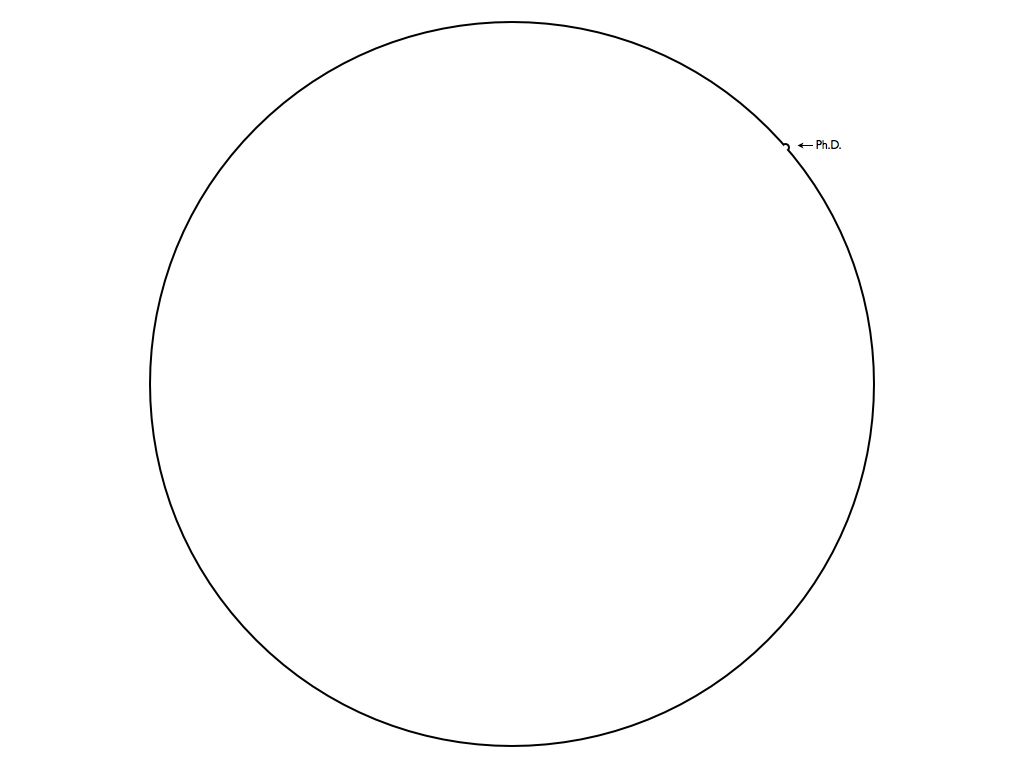

Imagine a circle that contains all of human knowledge.

By the time you finish elementary school, you know a little.

By the time you finish high school, you know a bit more.

With a bachelor's degree, you gain a specialty.

A master's degree deepens that specialty.

Reading research papers takes you to the edge of human knowledge.

[I modify the original text for the above slide to say that reading scholarly articles takes you to the edge of human knowledge. And then I tell them that this is why the English department stresses peer-reviewed, scholarly articles so much. Scholarly articles are where the truly deep, critical thinking is taking place. They're at the edge of human knowledge. So, if you want to improve your critical thinking, you need to read scholarly articles.]

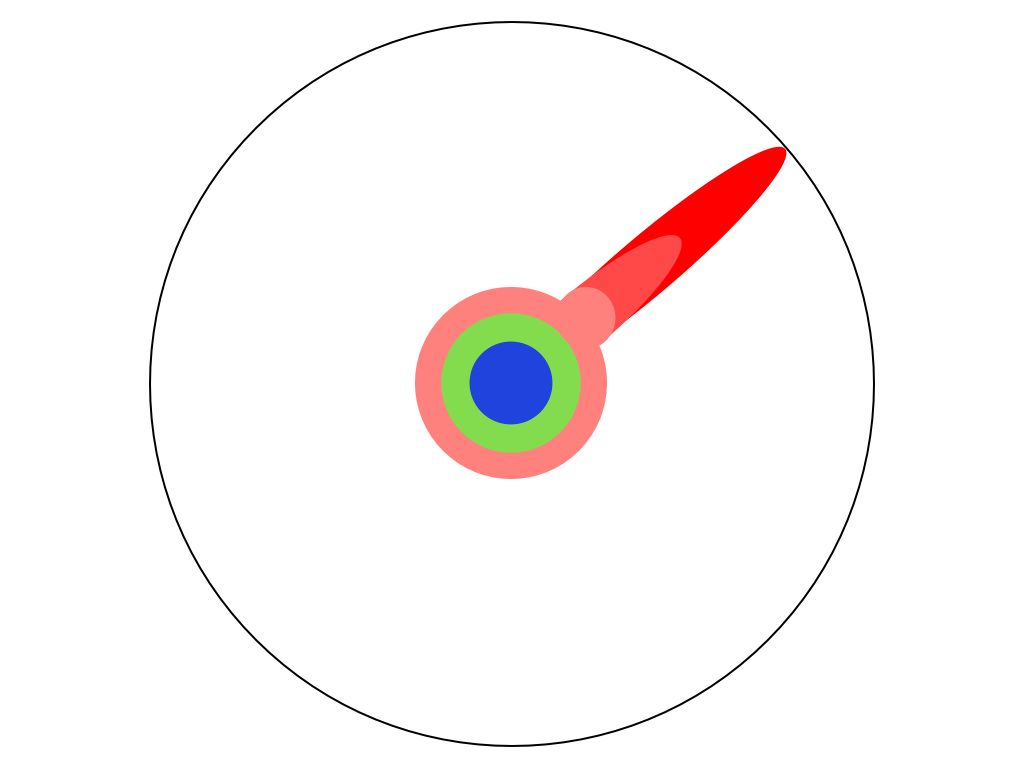

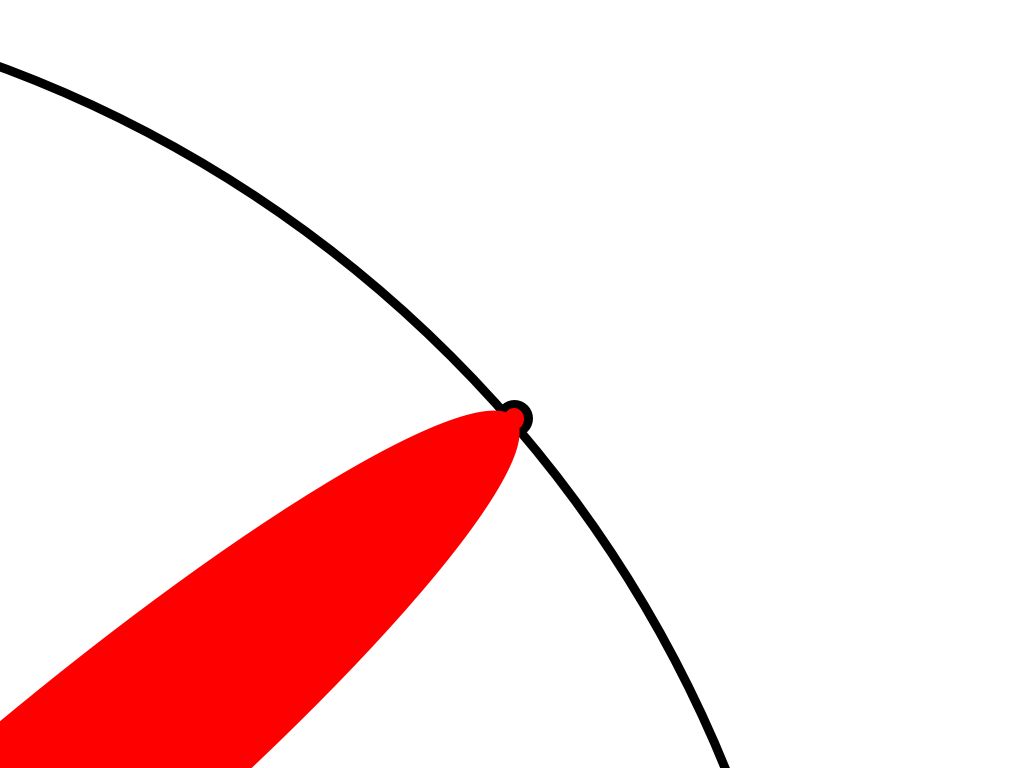

Once you’re at the boundary, you focus.

You push at the boundary for a few years.

Until one day, the boundary gives way.

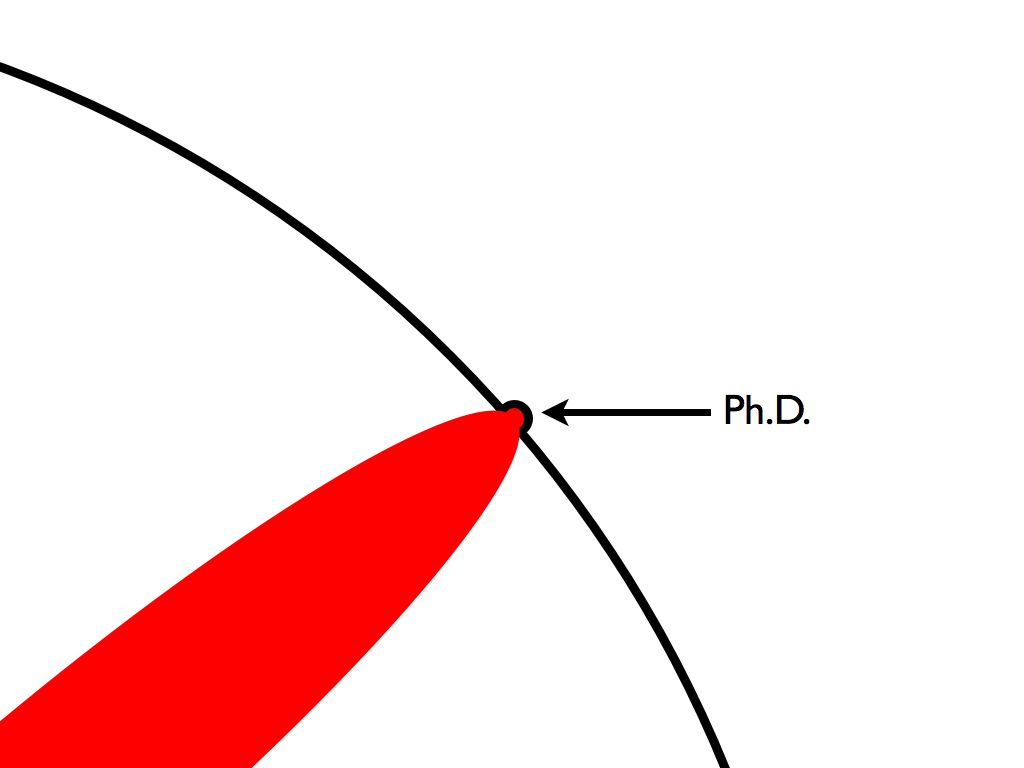

And that dent you’ve made is called a Ph.D.

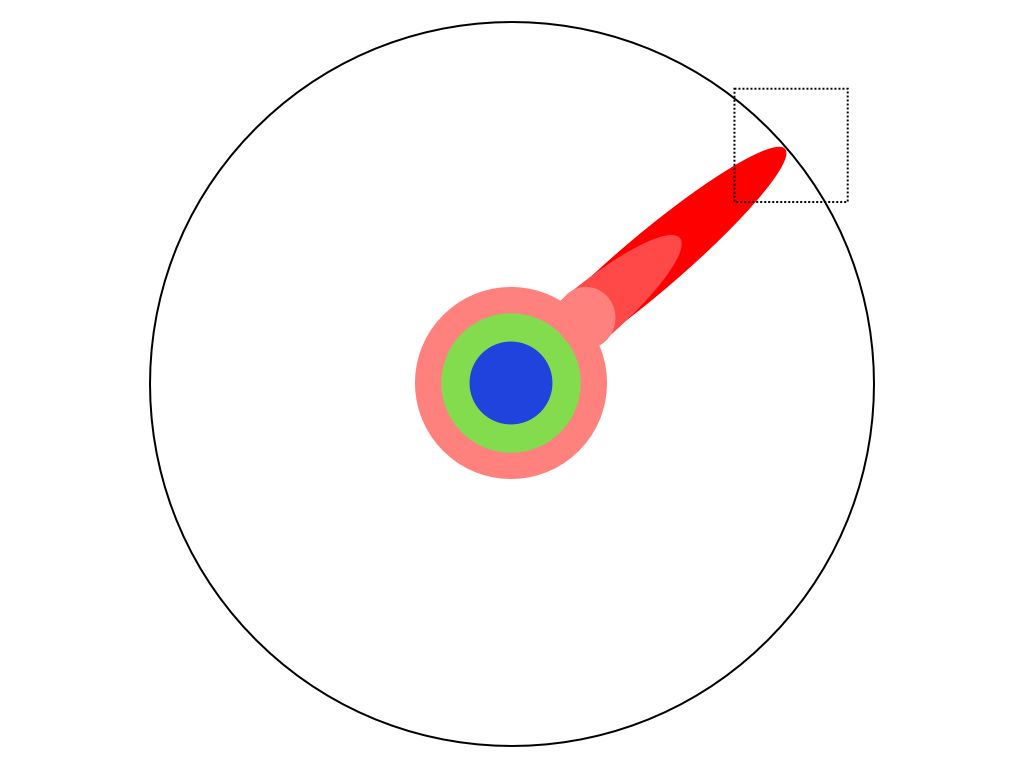

Of course, when you’ve reached this point, the world looks different to you now.

So don’t forget the big picture.

[On the above slide, I talk about how this is the purpose of research and scholarship: to expand the circle of human knowledge. All of us are benefited directly or indirectly by this process. I mention a story I heard on NPR's Planet Money about economist Tim Taylor who asks his students rather they'd prefer to be a middle income American living on $70,000 a year or a super-wealthy person in 1900 living on $70,000 a year. Approximately 2/3 of his students choose to be middle-income Americans because imagine all the things you'd do without: no antibiotics and other important medical procedures, no airplanes for easy travel abroad, no movie theaters or TV or Netflix or iPods, etc. The point is that the circle of human knowledge has expanded quite a bit in the last 100+ years. And we all benefit from those tiny little dents.]

[I then add something which wasn't in the original blog entry, but was a post script. I preface it by saying: "To put it a different way..."]

If you zoom in on the boundary of human knowledge in the direction of genetics, there’s something just outside of humanity’s reach. [The author of this has a son who was born with a rare, fatal genetic disorder. He discusses that he and his wife started funding graduate students after they learned about this.]

So... Keep pushing.

***

As for the rest of the lesson, I had required my students to bring a scholarly article to class this day and we spent the day talking about how to read scholarly articles, what their format is like, the best methods for reading them, etc. I then gave them about half an hour to read through their article and then we had an in-class discussion in which the students respond to what the experience was like.

For those students who were frustrated with the highly technical language, I go over some strategies for learning how to process what you read in scholarly articles better. (For more of my lecture notes---including strategies---or for the PowerPoint I created with the images above, feel free to email me.)

One of the awesome comments I got in class on Wednesday was from a student who said that reading his article was "surprisingly refreshing." He was reading some of the scholarship about Constitutional law and talked about how it was nice to actually read directly many of the things he hears glossed over in the mainstream media. I used that as a jumping off point for discussing how when you are reading scholarly articles, you're often reading primary research. So you're getting information direct from the source, free from mediating forces that interpret the information for you. You get to make up your own mind about the topic when you read scholarly articles.

I hope some of these ideas are helpful to you as you work on encouraging your students to engage with scholarly texts! Any pointers you have to share?